How Many Us Eligible Registered To Vote

Americans voted in record numbers in concluding year'south presidential election, casting virtually 158.4 meg ballots. That works out to more than six-in-ten people of voting age and well-nigh ii-thirds of estimated eligible voters, according to a preliminary Pew Inquiry Eye analysis.

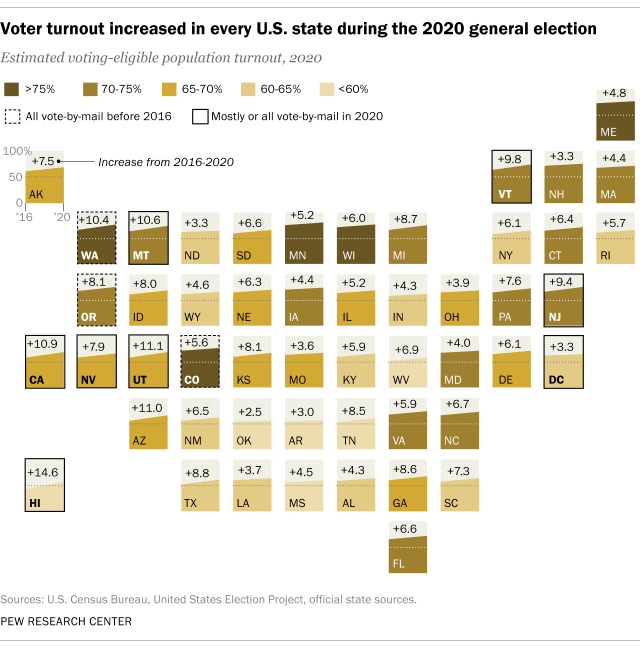

Nationwide, presidential election turnout was about seven percentage points higher than in 2016, regardless of which of three different turnout metrics we looked at: the estimated voting-age population equally of July one, that estimate adjusted to Nov. ane, and the estimated voting-eligible population, which subtracts noncitizens and ineligible felons and adds overseas eligible citizens. Based on these measures, turnout was the highest since at least 1980, the earliest twelvemonth in our assay, and perhaps much longer.

The ascension in turnout was fueled in part by the bitter fight betwixt incumbent President Donald Trump and challenger Joe Biden: A preelection survey found a record share of registered voters (83%) saying it "actually thing[ed]" who won. Merely another big factor was the dramatic steps many states took to expand mail balloting and early voting because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Turnout rates increased in every land compared with 2016, only of the x states where it rose the most, seven conducted November's vote entirely or mostly by mail, our assay shows. Half dozen of those states had recently adopted all-postal service voting, either permanently (Utah and Hawaii) or for the 2020 elections but (California, New Jersey, Vermont and most of Montana).

The past two months have been among the most turbulent post-ballot periods in American history, with unfounded but constantly repeated claims of voting fraud culminating in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol past a mob of Trump supporters. Given the standing divides over the 2020 presidential ballot, we wanted to put the bodily, verified turnout into some broader context. (The Census Bureau typically releases a detailed report on registration and voting after every national ballot, simply that's not likely to come up out for several months yet.)

Measuring U.South. voter turnout is 1 of those things that seems intuitively straightforward just in practise is annihilation but. U.S. elections are run not past a single national agency, equally in many other avant-garde democracies, but by individual states and counties within states. At that place is no central registry of eligible voters, no uniform rules for keeping registrations current, and no requirement to report vote totals in a consequent way.

All of which means that computing turnout rates inevitably involves judgment calls – both in choosing which votes to include (the numerator) and the population against which to compare them (the denominator).

For this post, we originally wanted to base our analysis on total ballots counted, a metric that includes all ballots regardless of offices voted for. (It's typically slightly higher than the presidential vote, since there are always some voters who skip that contest but vote in downwards-ballot races.) But not all states have reported total-ballots data, and so we turned our attending to the presidential race, which nearly e'er is the ane that attracts the nigh votes.

We compiled the official votes cast and counted for all presidential candidates (including write-in votes, when available) in 2016 and 2020, every bit certified and reported by each state'due south main election function. For the 2000, 2004, 2008 and 2012 elections, for which nosotros only needed aggregate nationwide vote totals, we relied on Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, supplemented when necessary by data from the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives.

For comparative purposes, we calculated the presidential-vote totals every bit percentages of iii separate measures of the potential voter pool: the xviii-and-over population as of July one, every bit estimated by the Census Bureau; those numbers interpolated to Nov. ane by Michael McDonald, a political scientist and turnout proficient at the University of Florida; and McDonald's estimate of the voting-eligible population, which subtracts noncitizens and ineligible felons and adds overseas eligible citizens.

Estimated turnout rates for other countries, which we've previously written virtually, were obtained from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, which works to promote and support democracy around the world.

In Hawaii, turnout rose from 42.3% of the estimated voting-eligible population in 2016 to 57% final year, the biggest turnout increase in the state by this measurement. In Utah, turnout increased by most 11 percentage points, from 56.8% of estimated eligible voters in 2016 to nearly 68% in 2020.

The smallest turnout increases, as shares of estimated eligible voters, were in Northward Dakota (3.3 percentage points), Arkansas (iii points) and Oklahoma (two.5 points). Interestingly, the District of Columbia's adoption of all-post voting for the 2020 election didn't seem to touch on turnout much: 63.seven% of estimated eligible D.C. voters voted for president, three.3 percentage points above the 2016 turnout level.

Minnesota had the highest turnout of whatever state last year, with 79.4% of estimated eligible voters casting ballots for president. Colorado, Maine and Wisconsin all followed close behind, at about 75.5%; Washington state, at 75.2%, rounded out the height five. The lowest-turnout states were Tennessee (59.6% of estimated eligible voters), Hawaii and Westward Virginia (57% each), Arkansas (55.9%) and Oklahoma (54.8%).

The Census Bureau will release its own estimates of turnout later this year, using a somewhat different methodology (people who say they voted every bit a share of estimated voting-age population). Just based on the pattern of previous years, information technology's likely the Census will show the highest turnout since the 1960s.

Despite the big bump in turnout last year, the U.S. nonetheless lags behind most of its developed-nation peers when information technology comes to electoral participation. Out of 35 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development for which estimates of voting-age population in the most contempo national election were bachelor, U.S. turnout ranked an underwhelming 24th.

How Many Us Eligible Registered To Vote,

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/28/turnout-soared-in-2020-as-nearly-two-thirds-of-eligible-u-s-voters-cast-ballots-for-president/

Posted by: nealeycubled.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Many Us Eligible Registered To Vote"

Post a Comment